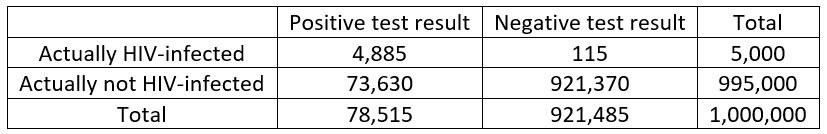

#15 How confident are you? part 2

How confident are you that your students can interpret a 95% confidence interval (CI) correctly? This post continues the previous one (here) by considering numerical data and highlighting a common misconception about interpreting a CI for a population mean.

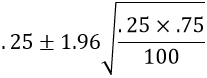

Here is the formula for a one-sample t-interval for a population mean μ, using conventional notation:

It’s worth making sure that students understand this notation. Two quiz questions that I often ask are: 1.Remind me: what’s the difference between μ and x-bar? 2. Remind me of what the symbol s stands for, and be sure to use three words in your response. Of course,I want students to say that μ is the symbol for a population mean and x-bar for a sample mean. I also hope they’ll say that s stands for a sample standard deviation. If they respond only with standard deviation, I tell them that this response is too vague and does not earn full credit.

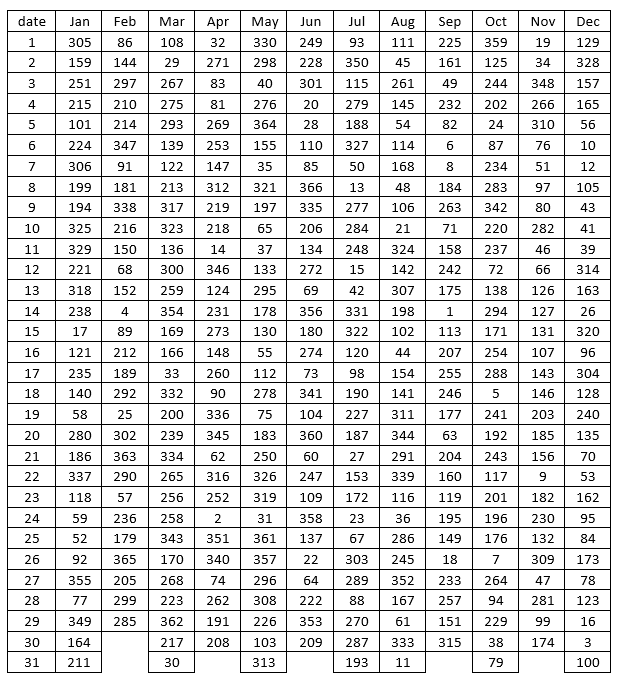

Let’s dive in to an example that we’ll use throughout this post: I’d like to estimate the average runtime of a feature film in the thriller genre. I selected a simple random sample of 50 thriller films from the population of 28,369* thrillers listed at IMDb (here).

* There are actually 41,774 feature films in the thriller genre listed at IMDb on October 13, 2019, but runtimes are provided for only 28,369 of them.

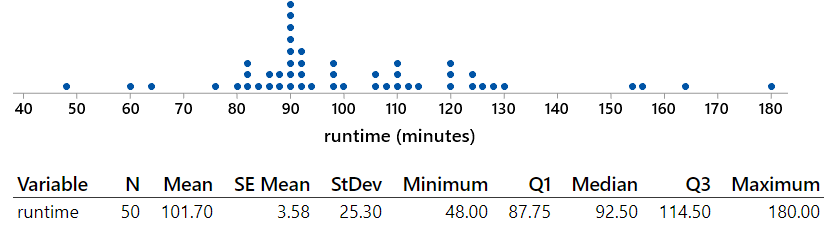

Consider the following (Minitab) output of the sample data:

My questions for students are:

- (a) What are the observational units and variable? What type of variable is this?

- (b) Describe the relevant population and parameter. Also indicate an appropriate symbol for this parameter.

- (c) Identify the appropriate confidence interval procedure.

- (d) Are the technical conditions for this procedure satisfied? Explain.

- (e) Calculate a 95% confidence interval for the population mean.

- (f) Interpret this interval.

- (g) What percentage of the films in the sample have times that fall within this interval?

- (h) Is this percentage close to 95%? Should it be? Explain what went wrong, or explain that nothing went wrong.

Here are my answers:

- (a) The observational units are the films. The variable is the runtime of the film, measured in minutes, which is a numerical variable.

- (b) The population is all feature films in the thriller genre listed at IMDb for which runtimes are provided. The parameter is the mean (average) runtime among these flims, denoted by μ.

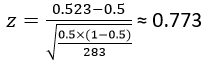

- (c) We will use a one-sample t-interval procedure to estimate the population mean μ.

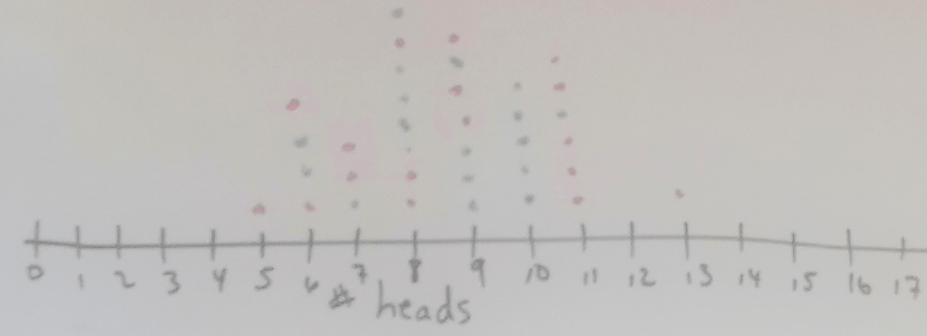

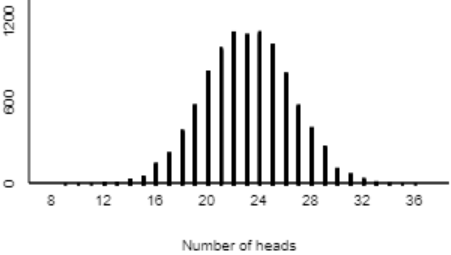

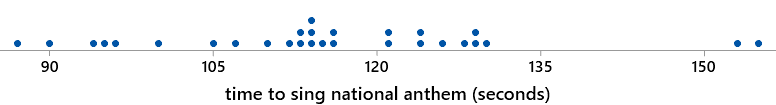

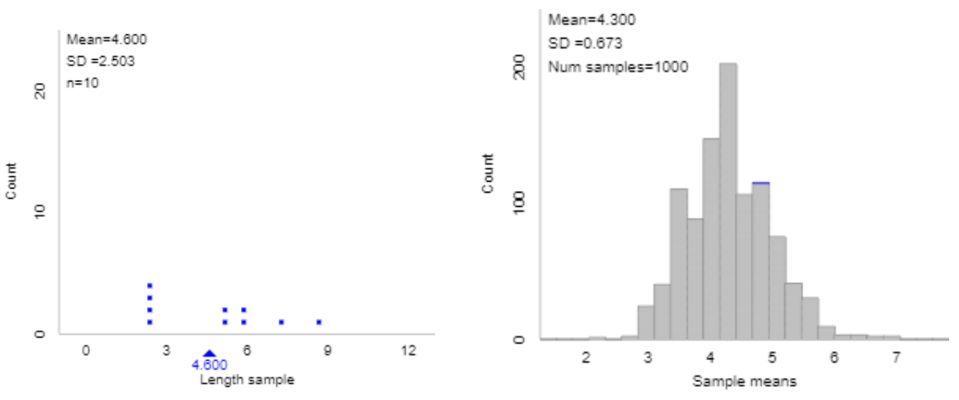

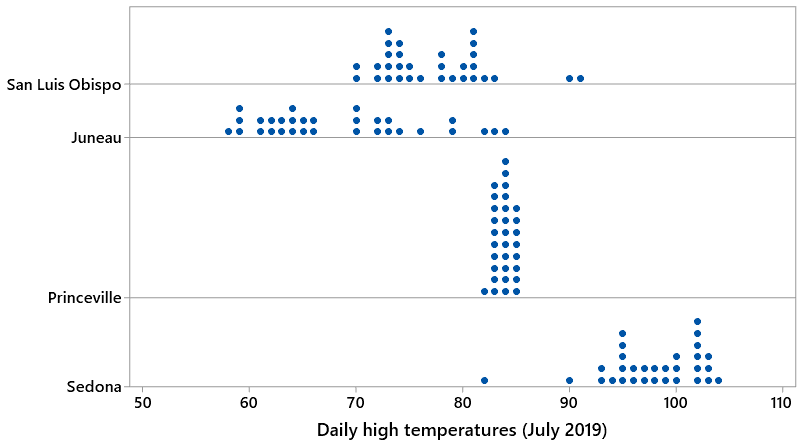

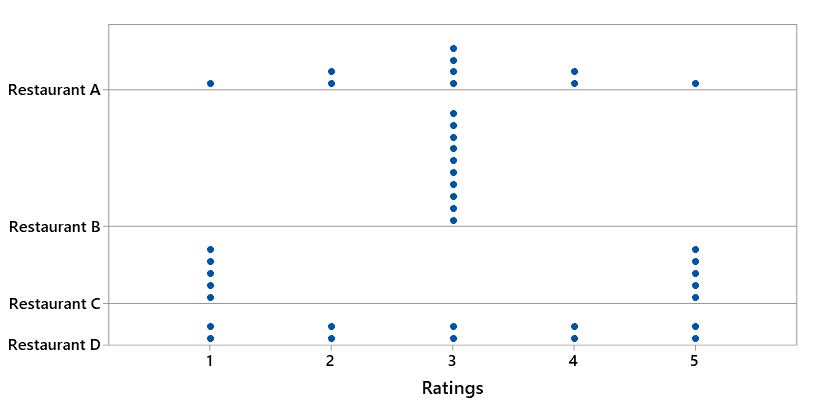

- (d) The dotplot of the sample data reveals that the distribution of runtimes is skewed to the right. But the skewness is not extreme, so the sample size of 50 films should be large enough for the t-interval procedure to be valid.

- (e) The 95% CI for μ is calculated as: 101.70 ± 2.010×25.30/sqrt(50), which is 101.70 ± 7.19, which is the interval (94.51 → 108.89) minutes.

- (f) We are 95% confident that the population mean runtime of a feature film in the thriller genre in IMDb is between 94.51 and 108.89 minutes.

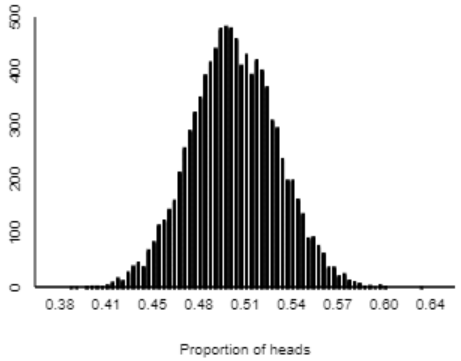

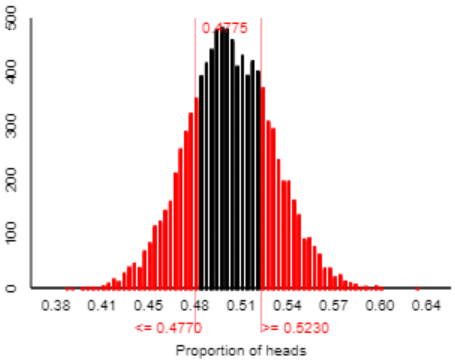

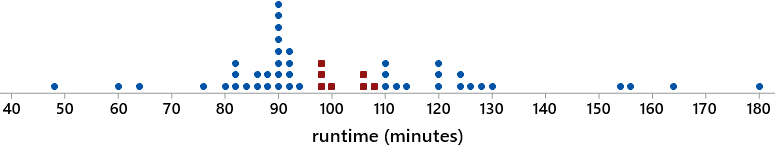

- (g) Only 7 of the 50 films (14%) run for more than 94.51 minutes and less than 108.89 minutes, as shown in red in this dotplot:

- (h) This percentage (14%) is nowhere close to 95%. Moreover, there’s no reason to expect this percentage to be close to 95%. Nothing went wrong here. Remember that the CI is estimating the population mean (average), not individual values. We do not expect 95% of the individual films’ runtimes to be within this CI. Rather, we are 95% confident that the population mean of the runtimes is within this CI.

Question (h) indicates a very common and troublesome student misconception. Many students mistakenly believe that a 95% CI for a population mean is supposed to contain 95% of the data values. These students are confusing confidence about a parameter with prediction about an individual. How can we help them to see the mistake here? I hope that questions (g) and (h) help with this, as students should see for themselves that only 7 of the 50 films (14%) in this sample fall within the CI. You might also point out that as the sample size increases, the CI for μ will continue to get narrower, so the interval will include fewer and fewer data values. We can also be sure to ask students to identify parameters in words as often as possible, because I think this misconception goes back to not paying enough attention to what a parameter is in the first place.

Something else we could consider doing* to help students to distinguish between confidence and prediction is to teach them about prediction intervals, which estimate individual values rather than the population mean. In many situations the relevant question is one of prediction. For example, you might be much more interested in predicting how long the next thriller film that you watch will take, as opposed to wanting to estimate how long a thriller film lasts on average.

* I confess that I do not typically do this, except in courses for mathematically inclined students such as those majoring in statistics, mathematics, or economics.

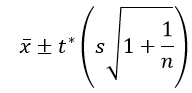

Here is the formula for a prediction interval:

Comparing this to the confidence interval formula above, we see that the prediction interval formula has an extra s (sample standard deviation) term. This accounts for variability from individual to individual, which makes the prediction interval much wider than the confidence interval. For the sample data on runtimes of thriller films, the 95% prediction interval is: 101.70 ± 2.010×25.30×sqrt(1+1/50), which is 101.70 ± 51.36, which is the interval (50.34 → 153.06) minutes. Notice how wide this interval is: Its half-width is 51.36 minutes (nearly an hour), compared to a half-width of just 7.19 minutes for the confidence interval above. This prediction interval captures 45 of the 50 runtimes in this sample (90%).

An important caveat is that unlike the t-confidence interval procedure for a population mean, this prediction interval procedure relies heavily on the assumption of a normally distributed population, regardless of sample size. The runtime distribution is skewed to the right, so this t-prediction interval procedure is probably not valid. A simpler alternative is to produce a prediction interval by using the (approximate) 2.5th and 97.5th percentiles of the sample data. For this sample, we could use the second-smallest and second-largest runtime values, which gives a prediction interval of (60 → 163) minutes. This interval contains 48/50 (96%) of the runtimes in the sample.

Now let’s re-consider question (f), which asked for an interpretation of the confidence interval. Below are four possible student answers. As you read these, please think about whether or not you would award full credit for that interpretation:

- 1. We are 95% confident that μ is between 94.5 and 108.9.

- 2. We are 95% confident that the population mean is between 94.5 and 108.9 minutes.

- 3. We are 95% confident that the population mean runtime of a thriller film in the IMDb list is between 94.5 and 108.9 minutes.

- 4. We are 95% confident that the population mean runtime of a thriller film in the IMDb list is between 94.5 and 108.9 minutes. This confidence stems from knowing that 95% of all confidence intervals generated by this procedure would succeed in capturing the actual value of the population mean.

I hope we agree that none of these interpretations is flat-out wrong, and they get progressively better as we progress from #1 through #4. Where would you draw the line about deserving full credit? I would regard #3 as good enough. I think #1 and #2 fall short by not providing context. I view #4 as going beyond what’s needed because the question asked only for an interpretation of the interval, not for the meaning of the 95% confidence level. I suggest asking a separate question specifically about interpreting confidence level*, in order to assess students’ understanding of that concept.

* I have asked: Explain what the phrase “95% confidence” means in this interpretation. This is a challenging question for most students.

Continuing this deep dive into into interpreting a confidence interval for a population mean, please consider the following incorrect answers. Think about which you consider to be more or less serious than others, and also reflect on which interpretations deserve full credit, partial credit, or no credit.

- A. We are 95% confident that a thriller film in the IMDb list runs for between 94.5 and 108.9 minutes.

- B. There’s a 95% chance that a thriller film in the IMDb list runs for between 94.5 and 108.9 minutes.

- C. About 95% of all thriller films in the IMDb list run for between 94.5 and 108.9 minutes.

- D. We are 95% confident that the mean runlength of a thriller film in this sample from the IMDb list was between 94.5 and 108.9 minutes.

- E. We are 95% confident that the mean runlength of a thriller film in a new random sample from the IMDb list would be between 94.5 and 108.9 minutes.

- F. There’s a 95% chance (or a 0.95 probability) that the population mean runlength of a thriller film in the IMDb list is between 94.5 and 108.9 minutes.

I contend that A, B, and C are all egregiously wrong. They all make the same mistake of thinking that the interval predicts the runtime of individual films rather than estimating a mean. I suppose you could say that A is better than B and C because it uses the word “confident.” In fact, simply inserting “on average” at the end of the sentence would be sufficient to fix A. But the idea of “on average” is a crucial one to have omitted!

I believe that D and E are slightly less wrong than A, B, and C, because they do include the idea of mean. But they refer to a sample mean instead of the population mean. This is also a serious error and so would receive no credit in my class. I might say that D is worse than E, because we know for sure that the mean runtime in this sample is the midpoint of the confidence interval.

What about F? It’s not quite correct, because it uses the language of chance and probability rather than confidence. The population mean μ is a fixed value, so it’s not technically correct* to refer to the probability or chance that μ falls in a particular interval. What’s random is the confidence interval itself, because the interval obtained from this procedure would vary from sample to sample if we were to take repeated random samples from the population**. But I consider this distinction between confidence and probability to be fairly minor, especially compared to the much more substantive distinction between confidence and prediction. I would nudge a student who produced F toward more appropriate language but would award full credit for this interpretation.

* Unless we take a Bayesian approach, which I will discuss in a future post.

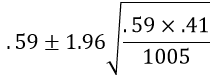

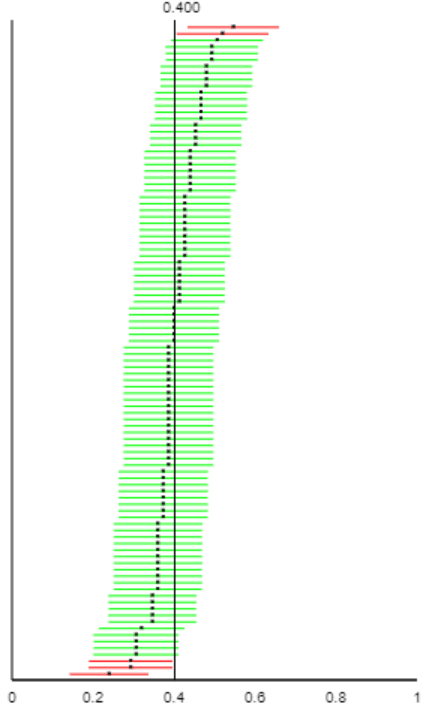

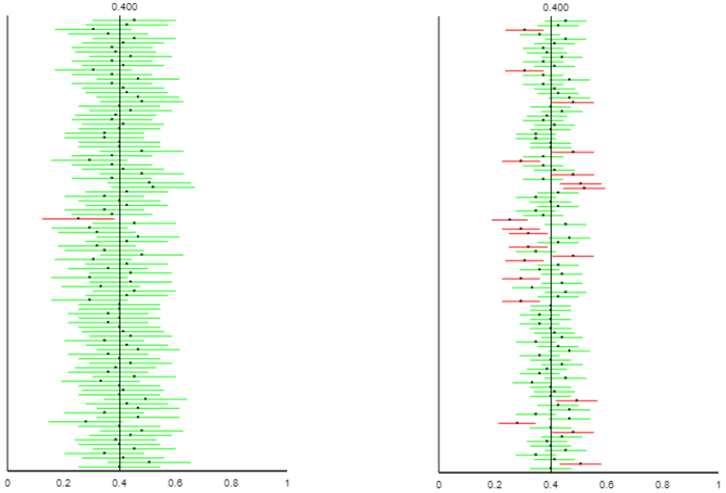

** As we saw in the previous post (here) by using the Simulating Confidence Intervals applet (here).

I ask a version of the “do you expect 95% of the data to fall within the CI” question almost every time I ask about interpreting a confidence interval. I remember one student from many years ago who seemed to be either tickled or annoyed by my repeating this question so often. In response to such a question on the final exam, he wrote something like: “Boy, some students must get this wrong a lot because you keep asking about it. Okay, once again, my answer is …” You might be expecting me to conclude this post on an ironic note by saying that the student then proceeded to give a wrong answer. But no, he nailed it. He knew that we do not expect anywhere near 95% of the data values to fall within a 95% confidence interval for the population mean. I hope that this student would be tickled, and not annoyed, to see that I have now devoted most of a blog post to this misconception.

P.S. The sample data on runtimes can be found in the file below.