#45 Simulation-based inference, part 3

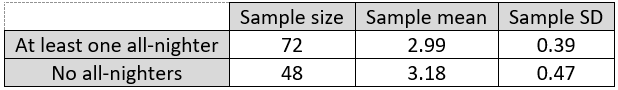

I’m a big believer in introducing students to concepts of statistical inference through simulation-based inference (SBI). I described activities for introducing students to the concepts of p-value and strength of evidence in posts #12 (here) and #27 (here). The examples in both of these previous posts concerned categorical variables. Now I will describe an activity for leading students to use SBI to compare two groups with a numerical response. As always, questions that I pose to students appear in italics.

Here’s the context for the activity: Researchers randomly assigned 14 male volunteers with high blood pressure to one of two diet supplements – fish oil or regular oil. The subjects’ diastolic blood pressure was measured at the beginning of the study and again after two weeks. Prior to conducting the study, researchers conjectured that those with the fish oil supplement would tend to experience greater reductions in blood pressure than those with the regular oil supplement*.

* I read about this study in the (wonderfully-titled) textbook The Statistical Sleuth (here). The original journal article can be found here.

a) Identify the explanatory and response variables. Also classify each as categorical or numerical.

I routinely ask this question of my students at the start of each activity (see post #11, Repeat after me, here). The explanatory variable is type of diet supplement, which is categorical and binary. The response variable is reduction in diastolic blood pressure, which is numerical.

b) Is this a randomized experiment or an observational study? Explain.

My students know to expect this question also. This is a randomized experiment, because researchers assigned each participant to a particular diet supplement.

c) State the hypotheses to be tested, both in words and in symbols.

I frequently remind my students that the null hypothesis is typically a statement of no difference or no effect. In this case, the null hypothesis stipulates that there’s no difference in blood pressure reductions, on average, between those who could be given a fish oil supplement as compared a regular oil supplement. The null hypothesis can also be expressed as specifying that the type of diet supplement has no effect on blood pressure reduction. Because of the researchers’ prior conjecture, the alternative hypothesis is one-sided: Those with a fish oil supplement experience greater reduction in blood pressure, on average, than those with a regular oil supplement.

In symbols, these hypotheses can be expressed as H0: mufish = mureg vs. Ha: mufish > mureg. Some students use x-bar symbols rather than mu in the hypotheses, which gives me an opportunity to remind them that hypotheses concern population parameters, not sample statistics.

I try to impress upon students that hypotheses can and should be determined before the study is conducted, prior to seeing the data. I like to reinforce this point by asking them to state the hypotheses before I show them the data.

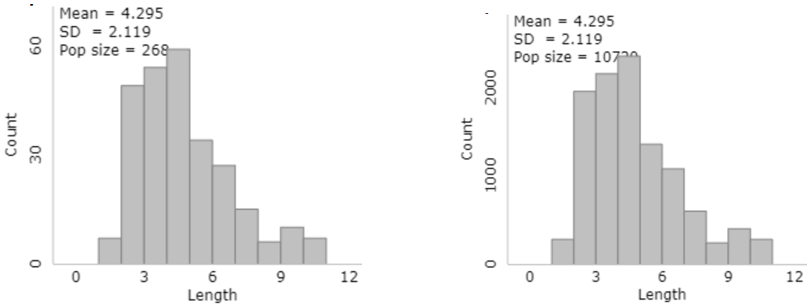

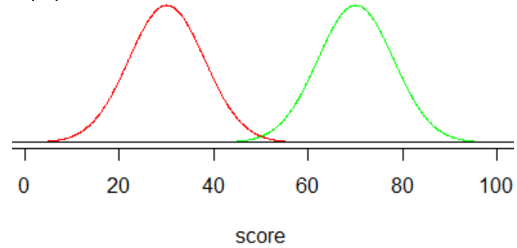

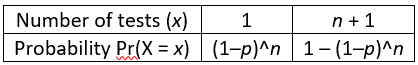

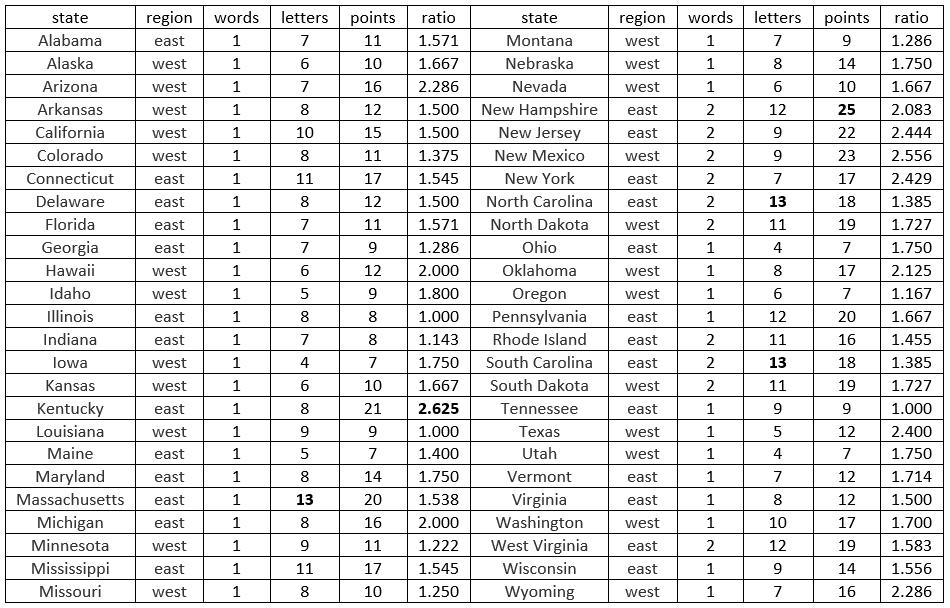

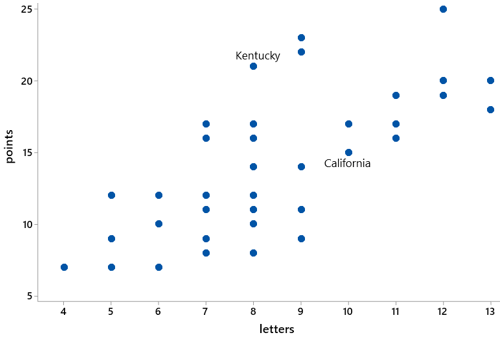

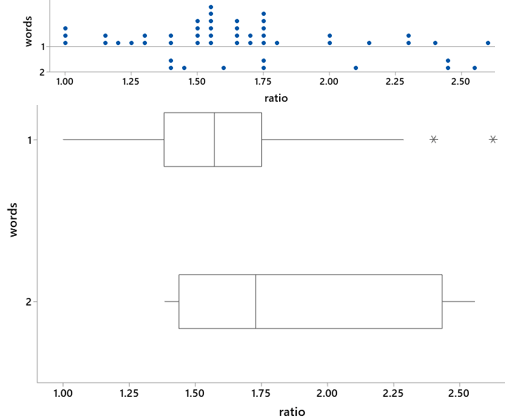

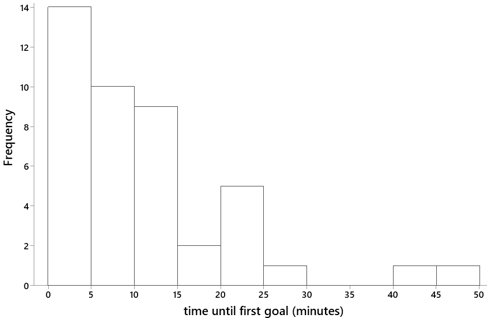

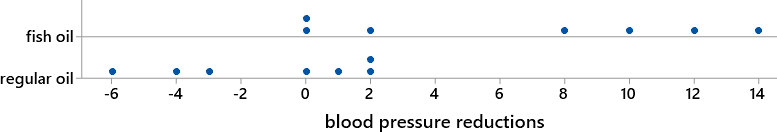

Here are dotplots showing the sample data on reductions in systolic blood pressure (measured in millimeters of mercury) for these two groups (all data values are integers):

d) Calculate the average blood pressure reduction in each group. What symbols do we use for these averages? Also calculate the difference in these group means (fish oil group minus regular oil group). Are the sample data consistent with the researchers’ conjecture? Explain.

The group means turn out to be: x-barfish = 46/7 ≈ 6.571 mm for the fish oil group, x-barreg = -8/7 ≈ -1.143 for the regular oil group. This difference is 54/7 ≈ 7.714 mm. The data are consistent with the researchers’ conjecture, because the average reduction was greater with fish oil than with regular oil.

e) Is it possible that there’s really no effect of the fish oil diet supplement, and random chance alone produced the observed differences in means between these two groups?

I remind students that they’ve seen this question, or at least its very close cousin, before. We asked this same question about the results of the blindsight study, in which the patient identified the non-burning house in 14 of 17 trials (see post #12, here). We also asked this about the results of the penguin study, in which penguins with a metal band were 30 percentage points more likely to die than penguins without a metal band (see post #27, here). My students know that the answer I’m looking for has four letters: Sure, it’s possible.

But my students also know that the much more important question is: How likely is it? At this point in class I upbraid myself for using the vague word and ask: What does it mean here? I’m very happy when a student explains that I mean to ask how likely it is to obtain sample mean reductions at least 7.714 mm apart, favoring fish oil, if type of diet supplement actually has no effect on blood pressure reduction.

f) How can we investigate how surprising it would be to obtain results as extreme as this study’s, if in fact there were no difference between the effects of fish oil and regular oil supplements on blood pressure reduction?

Students have seen different versions of this question before also. The one-word answer I’m hoping for is: Simulate!

g) Describe (in detail) how to conduct the simulation analysis to investigate the question in part f).

Most students have caught on to the principle of simulation at this point, but providing a detailed description in this new scenario, with a numerical response variable, can be challenging. I follow up with: Can we simply toss a coin as we did with the blindsight study? Clearly not. We do not have a single yes/no variable. Can we shuffle and deal out cards with two colors? Again, no. The two colors represented success and failure, but we now have numerical responses. How can we use cards to conduct this simulation? Some students have figured out that we can write the numerical responses from the study onto cards. What does each card represent? One of the participants in the study. How many cards do we need? Fourteen, one for each participant. What do we do with the cards? Shuffle them. And then what? Separate them into two groups of 7 cards each. What does this represent? Random assignment of the 14 subjects into one of the two diet supplement groups. Then what? Calculate the average of the response values in each group. And then? Calculate the difference in those two averages, being careful to subtract in the same order that we did before: fish oil group minus regular oil group. Great, what next? This one often stumps students, until they remember that we need to repeat this process, over and over again, until we’ve completed a large number of repetitions.

Before we actually conduct this simulation, I ask:

h) Which hypothesis are we assuming to be true as we conduct this simulation? This gives students pause, until they remember that we always assume the null hypothesis to be true when we conduct a significance test. They can also state this in the context of the current study: that there’s no difference, on average, between the blood pressure reductions that would be achieved with a fish oil supplement versus a regular oil supplement. I also want them to think about how it applies in this case: How does this assumption manifest itself in our simulation process? This is a hard question. I try to tease out the idea that we’re assuming the 14 participants were going to experience whatever blood pressure reduction they did no matter which group they had been assigned to.

Now, finally, having answered all of these preliminary questions, we’re ready to do something. Sometimes I provide index cards to students and ask them to conduct a repetition or two of this simulation analysis by hand. But I often skip this part* and proceed directly to conduct the simulation with a computer.

* I never skip the by-hand simulation with coins in the blindsight study or with playing cards in the penguin study, because I think the tactile aspect helps students to understand what the computer does. But the by-hand simulation takes considerably more time in this situation, with students first writing the 14 response values on 14 index cards and later having to calculate two averages. My students have already conducted tactile simulations with the previous examples, so I trust that they can understand what the computer does here.

I especially like that this applet (here), designed by Beth Chance, illustrates the process of pooling the 14 response values and then re-randomly assigning them between the two groups. The first steps in using the applet are to clear the default dataset and enter (or paste) the data for this study. (Be sure to click on “Use Data” after entering the data.) The left side of the screen displays the distributions and summary statistics. Then clicking on “Show Shuffle Options” initiates simulation capabilities on the right side of the screen. I advise students to begin with the “Plot” view rather than the “Data” view.

i) Click on “Shuffle Responses” to conduct one repetition of the simulation. Describe what happens to the 14 response values in the dotplots. Also report the resulting value of the difference in group means (again taking the fish oil group minus the regular oil group).

This question tries to focus students’ attention on the fact that the applet is doing precisely what we described for the simulation process: pooling all 14 (unchanging) response values together and then re-randomizing them into two groups of 7.

j) Continue to click on “Shuffle responses” for a total of 10 repetitions. Did we obtain the same result (for the difference in group means) every time? Are any of the difference in groups means as large as the value observed in the actual study: 7.714 mm?

Perhaps it’s obvious that the re-randomizing does not produce the same result every time, but I think this is worth emphasizing. I also like to keep students’ attention on the key question of how often the simulation produces a result as extreme as the actual study.

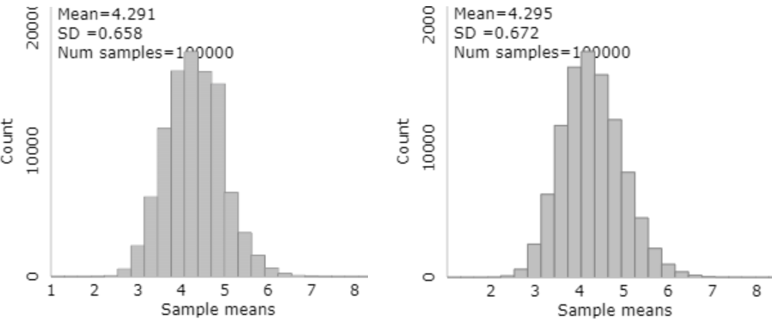

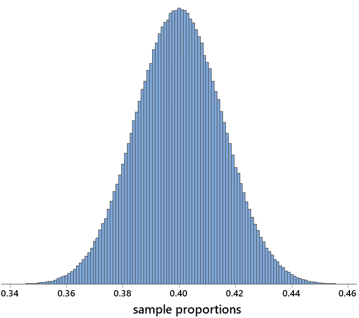

k) Now enter 990 for the number of shuffles, which will produce a total of 1000 repetitions. Consider the resulting distribution of the 1000 simulated differences in group means. Is the center where you would expect? Does the shape have a recognizable pattern? Explain.

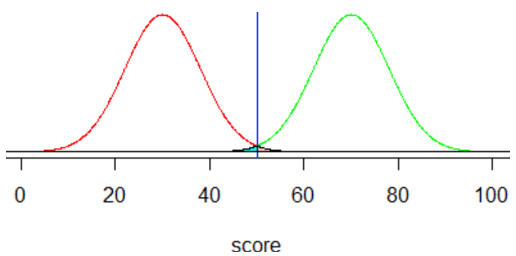

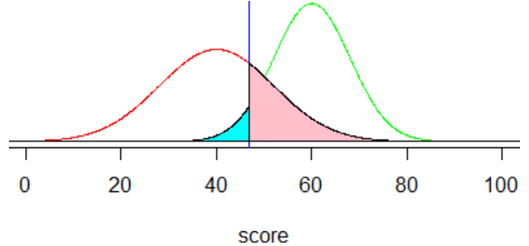

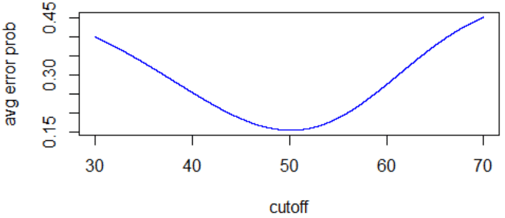

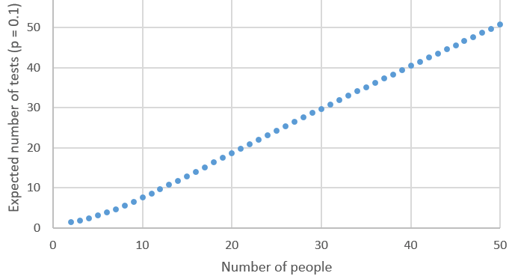

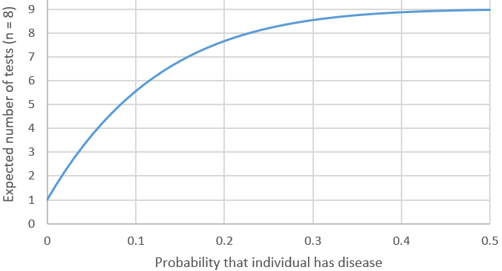

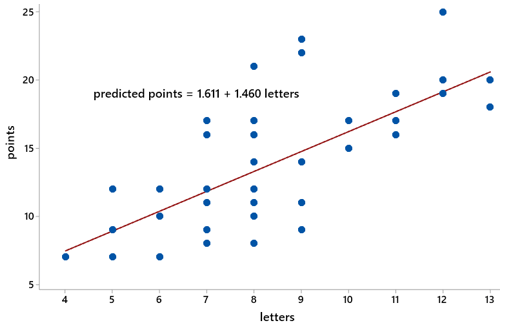

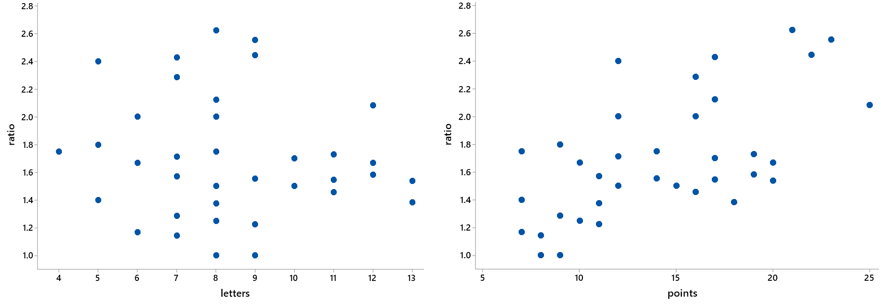

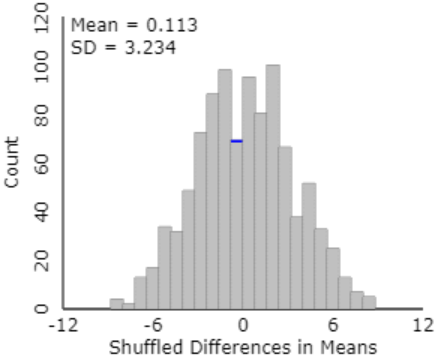

Here is some output from this simulation analysis:

The mean is very close to zero. Why does this make sense? The assumption behind the simulation is that type of diet supplement has no effect on blood pressure reduction, so we expect the difference in group means (always subtracting in the same order: fish oil group minus regular oil group) to include about half positive values and half negative values, centered around zero. The shape of this distribution is very recognizable at this point of the course: approximately normal.

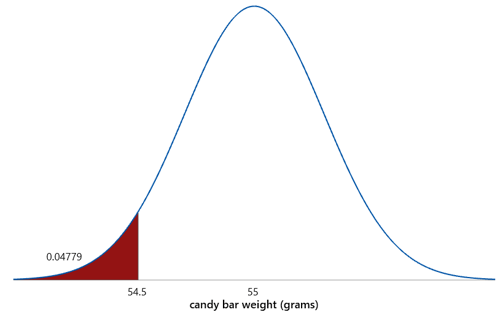

l) Use the Count Samples feature of the applet to determine the approximate p-value, based on the simulation results. Also describe how you determine this.

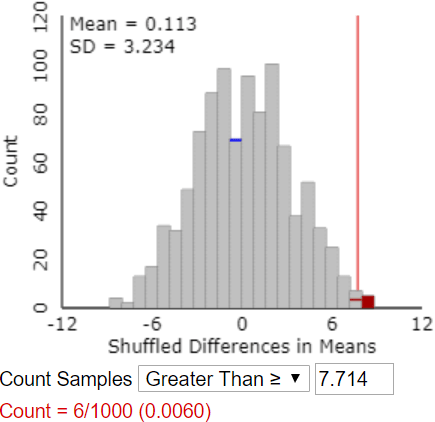

The applet does not have a “Calculate Approximate P-value” button. That would have been easy to include, of course, but the goal is for students to think through how to determine this for themselves. Students must realize that the approximate p-value is the proportion of the 1000 simulated differences in group means that are 7.714 or larger. They need to enter the value 7.714 in the box* next to “Count Samples Greater Than” and then click on “Count.” The following output shows an approximate p-value of 0.006:

* If a student enters a different value here, the applet provides a warning that this might not be the correct value, but it proceeds to do the count.

m) Interpret what this (approximate) p-value means.

This is usually a very challenging question. But based on simulation-based inference, students need not memorize this interpretation of a p-value. Instead, they simply have to describe what’s going on in the graph of simulation results: If there were no effect of diet supplement on blood pressure reductions, then about 0.6% of random assignments would produce a difference in sample means, favoring the fish oil group, of 7.714 or greater. I also like to model conveying this idea with a different sentence structure, such as: About 0.6% of random assignments would produce a difference in sample means, favoring the fish oil group, of 7.714 or greater, assuming that there were no effect of diet supplement on blood pressure reductions. The hardest part of this for most students is remembering to include the if or assuming part of this sentence.

Now we are ready to draw some conclusions.

n) Based on this simulation analysis, do the researchers’ data provide strong evidence that the fish oil supplement produces a greater reduction in blood pressure, on average, than the regular oil supplement? Also explain the reasoning process by which your conclusion follows from the simulation analysis.

The short answer is yes, the data do provide strong evidence that the fish oil supplement is more helpful for reducing blood pressure than the regular oil supplement. I hope students answer yes because they understand the reasoning process, not because they’ve memorized that a small p-value means strong evidence of … I do not consider “because the p-value is small” to be an adequate explanation of the reasoning process. I’m looking for something such as: “It would be very unlikely to obtain a difference in group mean blood pressure reductions of 7.714mm or greater, if fish oil were no better than regular oil. But this experiment did find a difference in group means of 7.714mm. Therefore, we have strong evidence against the hypothesis of no effect, in favor of concluding that fish oil does have a beneficial effect on blood pressure reduction.”

At this point I make a show of pointing out that I just used the important word effect, so I then ask:

o) Is it legitimate to draw a cause-and-effect conclusion between the fish oil diet and greater blood pressure reductions? Justify your answer.

Yes, a cause-and-effect conclusion is warranted here, because this was a randomized experiment and the observed difference in group means is unlikely to occur by random assignment alone if there were no effect of diet supplement type on blood pressure reduction.

Now that I’ve asked about causation, I follow up with a final question about generalizability:

p) To what population is it reasonable to generalize the results of this study?

Because the study included only men, it seems unwise to conclude that women would necessarily respond to a fish oil diet supplement in the same way. Also, the men in this study were all volunteers who suffered from high blood pressure. It’s probably best to generalize only to men with high blood pressure who are similar to those in this study.

Whew, that was a lot of questions*! I pause here to give students a chance to ask questions and reflect on this process. I also reinforce the idea, over and over, that this is the same reasoning process they’ve seen before, with the blindsight study for a single proportion and with the penguin study for comparing proportions. The only difference now is that we have a numerical response, so we’re looking at the difference in means rather than proportions. But the reasoning process is the same as always, and the interpretation of p-value is the same as always, and the way we assess strength of evidence is the same as always.

* We didn’t make it to part (z) this time, but this post is not finished yet …

Now I want to suggest three extensions that you could consider, either in class or on assignments, depending on your student audience, course goals, and time constraints. You could pursue any or all of these, in any order.

Extension 1: Two-sample t-test

q) Conduct a two-sample t-test of the relevant hypotheses. Report the value of the test statistic and p-value. Also summarize your conclusion.

The two-sample (unpooled) test statistic turns out to be t = 3.06, with a (one-sided) p-value of ≈ 0.007*. Based on this small p-value, we conclude that the sample data provide strong evidence that fish oil reduced blood pressure more, on average, than regular oil.

* Whenever this fortunate occurrence happens, I tell students that this is a p-value of which James Bond would be proud!

r) How does the result of the t-test compare to that of the simulation analysis?

The result are very similar. The approximate p-value from the simulation analysis above was 0.006, and the t-test gave an approximate p-value of 0.007.

Considering how similar these results are, you might be wondering why I recommend bothering with the simulation analysis at all. The most compelling reason is that the simulation analysis shows students what a p-value is: the probability of obtaining such a large (or even larger) difference in group means, favoring the fish oil group, if there were really no difference between the treatments. I think this difficult idea comes across clearly in the graph of simulated results that we discussed above. I don’t think calculating a p-value from a t-distribution helps to illuminate this concept.

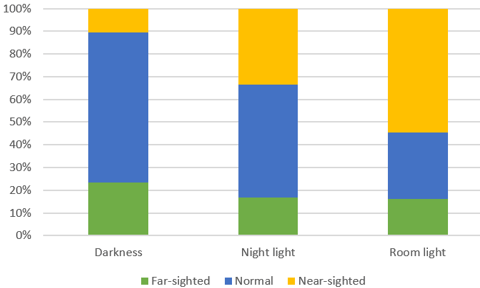

Extension 2: Comparing medians

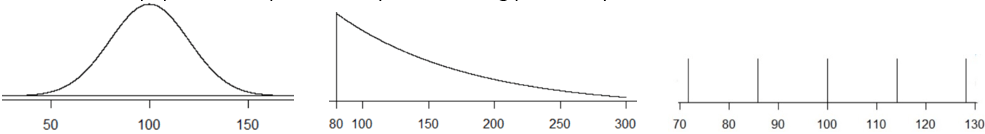

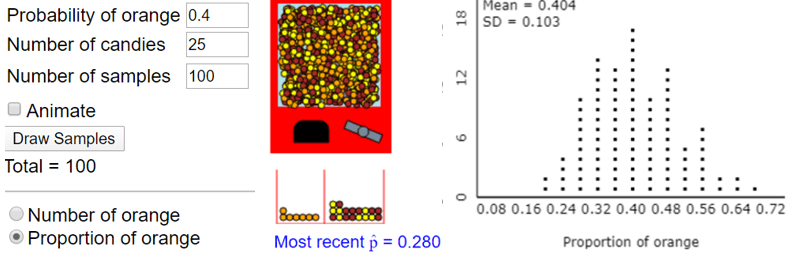

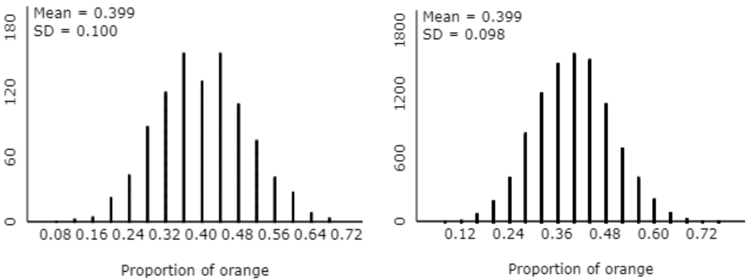

Another advantage of simulation-based inference is that it provides considerable flexibility with regard to the choice of statistic to analyze. For example, could we compare the medians of the two groups instead of their means? From the simulation-based perspective: Sure! Do we need to change the analysis considerably? Not at all! Using the applet, we simply select the difference in medians rather than the difference in means from the pull-down list of statistic options on the left side. If we were writing our own code, we would simply replace mean with median.

s) Before we conduct a simulation analysis of the difference in median blood pressure reductions between the two groups, first predict what the distribution of 1000 simulated differences in medians will look like, including the center and shape of the distribution.

One of these is much easier to anticipate than the other: We can expect that the center will again be near zero, again because the simulation operates under the assumption of no difference between the treatments. But medians often do not follow a predictable, bell-shaped curve like means often do, especially with such small sample sizes of 7 per group.

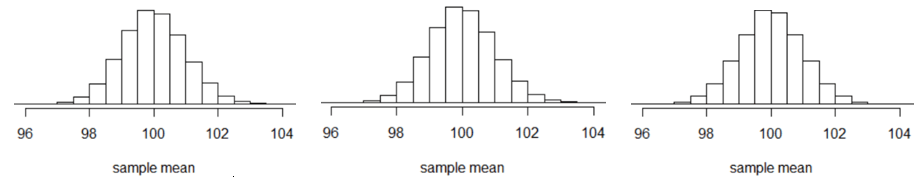

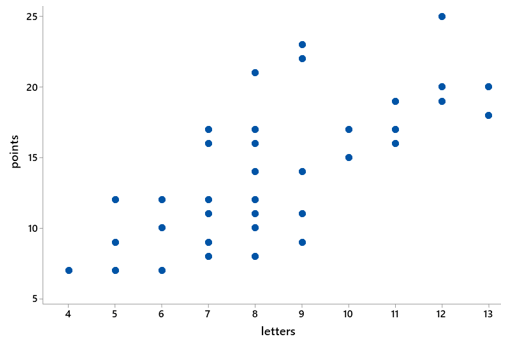

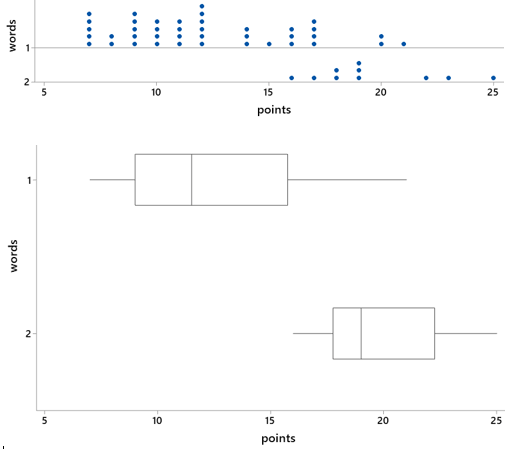

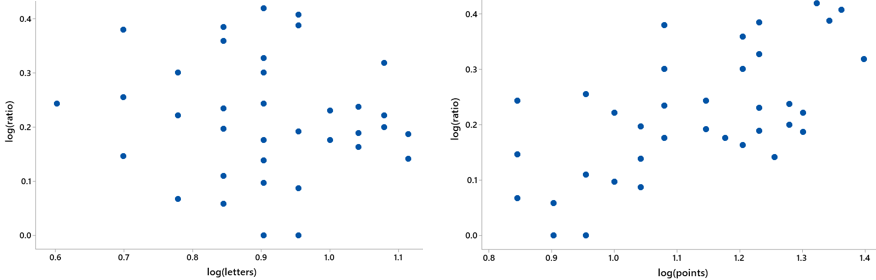

t) Use the applet to conduct a simulation analysis with 1000 repetitions, examining the difference in medians between the groups. Describe the resulting distribution of the 1000 simulated differences in medians.

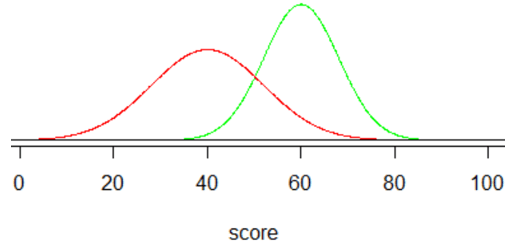

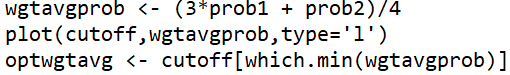

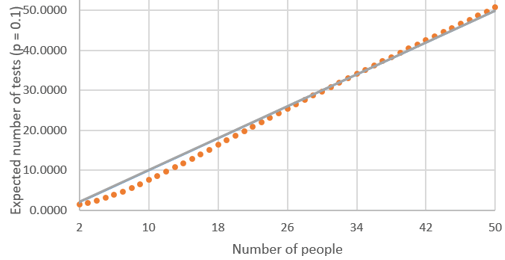

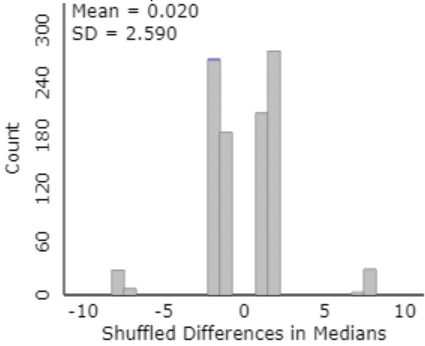

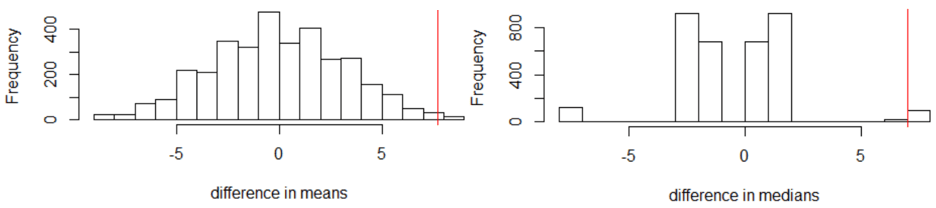

Here is some output:

The center is indeed close to zero. The shape of this distribution is fairly symmetric but very irregular. This oddness is due to the very small sample sizes and the many duplicate data values. In fact, there are only eight possible values for the difference in medians: ±8, ±7, ±2, and ±1.

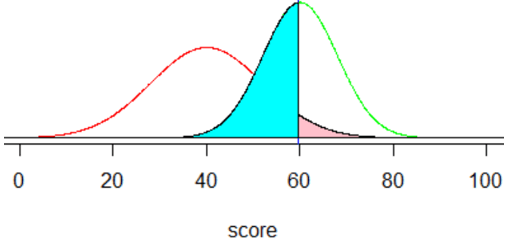

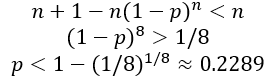

u) How do we determine the approximate p-value from this simulation analysis? Go ahead and calculate this.

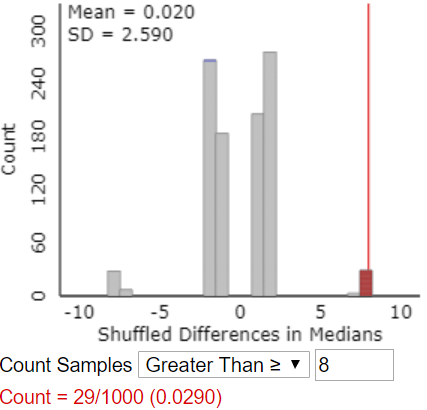

This question makes students stop and think. I really want them to be able to answer this correctly, because they’re not really understanding simulation-based inference if they can’t. I offer a hint: Do we plug in 7.714 again and count beyond that value? Most students realize that the answer is no, because 7.714 was the difference in group means, not medians, in the actual study. Then where do we count? Many students see that we need to count how often the simulation gave a result as extreme as the difference in medians in the actual study, which was 8mm.

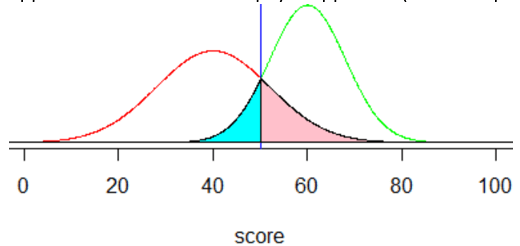

Here’s the same graph, with results for which the difference in sample medians is 8 or greater colored in red:

v) Compare the results of analyzing medians rather than means.

We obtained a much smaller p-value when comparing means (0.006) than when comparing medians (0.029). In both cases, we have reasonably strong evidence that fish oil is better than regular oil for reducing blood pressure, but we have stronger evidence based on means than on medians.

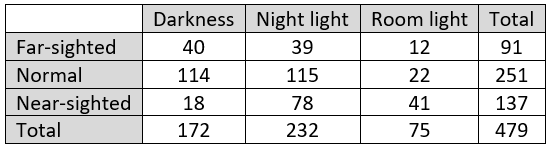

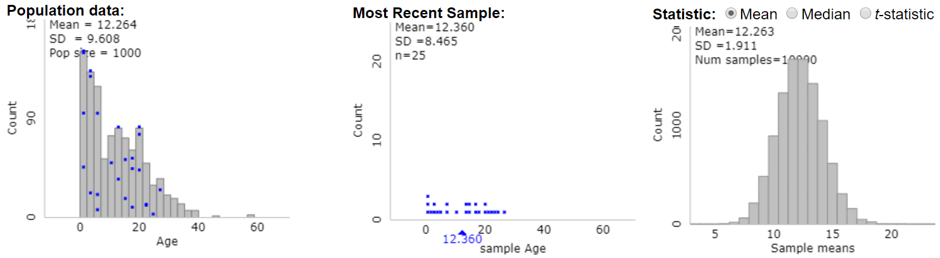

Extension 3: Exact randomization test

What we’ve simulated above is often called a randomization test. Could we determine the p-value for the randomization test exactly rather than approximately with simulation? Yes, in principle, but this would involve examining all possible ways to randomly assign subjects between the treatment groups. In most studies, there are often too many combinations to analyze efficiently. In this study, however, the number of participants is small enough that we can determine the exact randomization distribution of the statistic. I only ask the following questions in courses for mathematically inclined students.

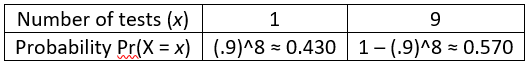

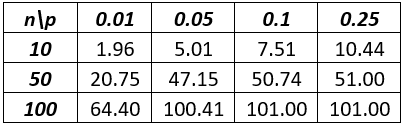

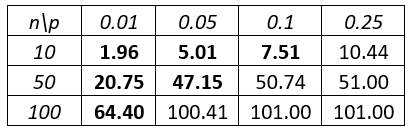

w) In many ways can 14 people be assigned to two groups of 7 people each?

This is what the combination (also called a binomial coefficient) 14-choose-7 tells us. This is calculated as: 14! / (7! ×7!) = 3432. That’s certainly too many to list out by hand, but that’s a pretty small number to tackle with some code.

x) Describe what to do, in principle, to determine the exact randomization distribution.

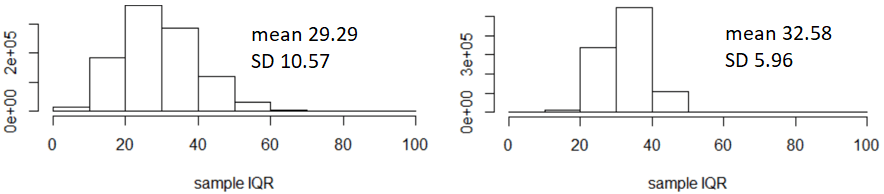

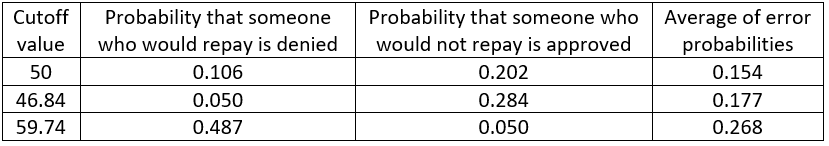

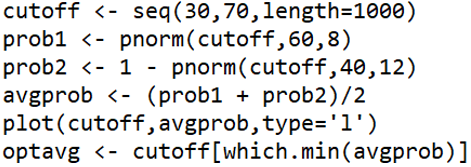

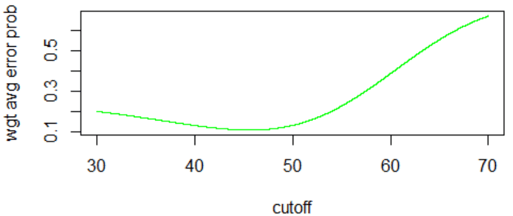

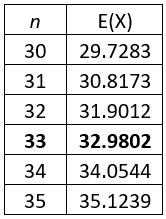

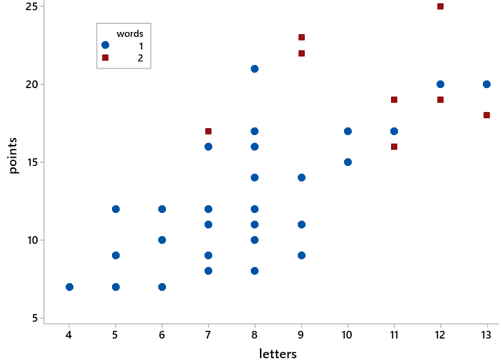

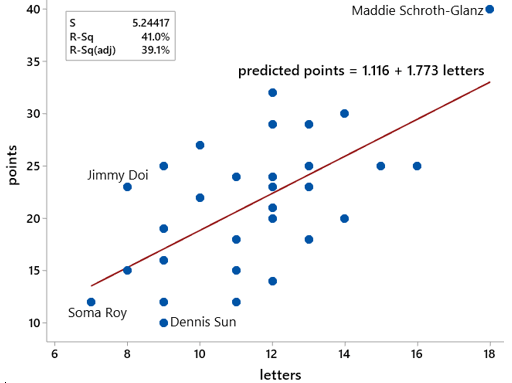

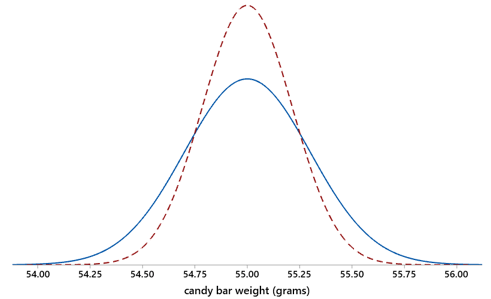

We continue to assume that the 14 participants were going to obtain the same blood pressure reduction values that they did, regardless of which diet supplement group they had been assigned to. For each of these 3432 ways to split the 14 participants into two groups of 7 each, we calculate the mean/median of data values in each group, and then we calculate the difference in means/medians (fish oil group minus regular oil group). I’ll spare you the coding details. Here’s what we get, with difference in means on the left, difference in medians on the right:

y) How would you calculate the exact p-values?

For the difference in means, we need to count how many of the 3432 possible random assignments produce a difference in means of 7.714 or greater. It turns out that only 31 give such an extreme difference, so the exact p-value is 31/3432 ≈ 0.009.

If we instead compare medians, it turns out that exactly 100 of the 3432 random assignments produce a difference in medians of 8 or greater, for a p-value of 100/3432 ≈ 0.029. Interestingly, 8 is the largest possible difference in medians, but there are 100 different ways to achieve this value from the 14 data values.

z) Did the simulation results come close to the exact p-values?

Yes. The approximate p-value based on comparing means was 0.006, very close to the exact p-value of 0.009. Similarly, the approximate p-value based on comparing medians was 0.029, the same (to three decimal places) as the exact p-value.

If you’re intrigued by simulation-based inference but reluctant to redesign your entire course around this idea, I recommend sprinkling a bit of SBI into your course. Depending on how many class sessions you can devote to this, I recommend these sprinkles in this order:

- Inference for a single proportion with a 50/50 null, as with the blindsight study of post #12 (here)

- Comparing two proportions, as with the penguin study of post #27 (here)

- Comparing two means or medians, as with the fish oil study in this post

- Inference for correlation, as with the draft lottery toward the end of post #9 (here)

For each of these scenarios, I strongly suggest that you introduce the simulation-based approach before the conventional method. This can help students to understand the logic of statistical inference before getting into the details. I also recommend emphasizing that the reasoning process is the same throughout these scenarios. After leading students through the simulation-based approach, you can impress upon students that the conventional methods are merely shortcuts that predict what the simulation results would look like without bothering to conduct the simulation.

P.S. Here is a link to the datafile for this activity:

P.P.S. I provided a list of textbooks that prominently include simulation-based inference at the end of post #12 (here).

P.P.P.S. I dedicate this post to George Cobb, who passed away in the last week. George had a tremendous impact on my life and career through his insightful and thought-provoking writings and also his kind mentoring and friendship.

George’s after-dinner address at the inaugural U.S. Conference on Teaching Statistics in 2005 inspired many to pursue simulation-based inference for teaching introductory statistics. His highly influential article based on this talk, titled “The Introductory Statistics Course: A Ptolemaic Curriculum?,” appeared in the inaugural issue of Technology Innovations in Statistics Education (here). George wrote: “Before computers statisticians had no choice. These days we have no excuse. Randomization-based inference makes a direct connection between data production and the logic of inference that deserves to be at the core of every introductory course.”

George’s writings contributed greatly as my Ask Good Questions teaching philosophy emerged. At the beginning of my career, I read his masterful article “Introductory Textbooks: A Framework for Evaluation,” in which he simultaneously reviewed 16 textbooks for the Journal of the American Statistical Association (here). Throughout this review George repeated the following mantra over and over: Judge a textbook by its exercises, and you cannot go far wrong. This sentence influenced me not only for its substance – what teachers ask students to do is more important than what teachers tell students – but also for its style – repeating a pithy phrase can leave a lasting impression.

Another of my favorite sentences from George, which has stayed in my mind and influenced my teaching for decades, is: Shorn of all subtlety and led naked out of the protective fold of education research literature, there comes a sheepish little fact: lectures don’t work nearly as well as many of us would like to think (here).

I had the privilege of interviewing George a few years ago for the Journal of Statistics Education (here). His wisdom, humility, insights, and humor shine throughout his responses to my questions.